Vlaminck was Fauvist and sometime Impressionist and a bit of a Cubist painter. The work I saw in the show impressed me as among the best (most aesthetically moving to me) of the genres in which he participated. His history and his art are a mix of greatness and pathos.

The Barberini Museum in Potsdam, DE, is a magnificent palace located in a grand European plaza. The context is not nothing. It is a palace of art. It’s true that in Germany there are a whole lot of palaces of art. In Berlin, for example, on “Museum Island,” there are five such palaces right on top of each other. Anything shown in such a place is glorified. It must be a burden to decide what to show. Isn’t it always, though?

From Berlin, you can take a commuter train directly to Potsdam, a smallish town, in half an hour. (One of the stops along the way is Wannsee. Couple of sites there: Max Lieberman’s house and the Wannsee Villa memorial to the conference in which the Nazis planned the “final solution” to the Jews. We didn’t get off at Wannsee. Later we did get to see some fine Lieberman paintings in the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin. I can imagine a short story about a professor of Hitler studies who feels the need to go to the Wansee villa. This post is not that.)

The Wannsee Villa. What is the relation between a beautiful house and what people do inside? Nothing. What is the relation between aesthetics and ethics?

Two issues were immediately striking for me seeing this show of Maurice Vlaminck’s paintings at the Barberini Museum in Potsdam. One was the way the museum chose Vlam as an aesthetically important history-of-art modern painter worthy of a show, and the other was his ambivalent role within his community, among his peers, and in his scene.

James Baldwin, in seeing the Swiss villagers as “European” in “Stranger in the Village,” saw them about as poorly as they saw him as a weirdo African, touching his hair and offending him every third sentence. Vlaminck was a white male Frenchman. As a person, he became, at times, a weak, narcissistic credit-seeker willing to throw his lot in with his oppressors. As a political object, his Europeanness isn’t a liability in the European context the way it might be for an American art institution. American whiteness isn’t the same as in Europe, where American whiteness supposedly comes from. Up close in Europe, there are some people who think of themselves as “European,” the way an American leftist might say a white person is of European descent, but living Euros think of themselves as part of national groups a lot more often. People grow up with a language, after all. Europeans learn many, but tend to call one “their” language. Vlaminck was French, not “white.” On the other hand, Vlaminck claimed, with reason, that he introduced Picasso to the artistic value of African masks, a claim with a somewhat different value than it had when Vlaminck made it. Nowadays, this claim might still give Vlaminck partial credit for Picasso’s Demoiselles D’Avignon, but it also marks him as having the typical European attitude toward colonialism and African culture of the early 20th-century: an ignorance and lack of curiosity that allowed these modern European artists to strip out the meanings the masks might have originally had, and use them as symbols of uncivilization.

No one can escape their recent past. Euros and especially Germans cannot escape their past of horrific nationalism. So much of what one sees in Berlin is determined or inflected by the way the people try to deal with the Nazi period and with its resulting split of Germany into two defeated countries until 1990. Berlin is nothing if not a city made up of its 20th century traumas, crimes, and horrors. And yet, I, as a Jew whose family either fled from Germany in the 1930s or were killed by the Germans in the 1940s, see things that others would not see. I am skewed. The eye altering alters all.

Why is this past at all relevant to the show of the French Fauvist?

This question gets some illumination from the other issue that comes up when reading about Vlaminck or looking at the work: the artist’s relationship to his peers and artistic movements.

A short info film about Vlaminck is shown on a loop in a small auditorium in the museum. You can see it on the Barberini website. The film talks about how he was part of a community of Cezanne-worshipping artists in France in 1905-6. Curator Anna Storm mentions a “Cezanne fever” at this time, with lots of Cezanne retrospectives. He was part of a scene. The intensity with which Cezanne re-made art after Impressionism is something I’ve been meaning to study and understand better for a long while. Vlaminck, like Picasso, Matisse, and everyone else around this time, owed much to Cezanne’s impressive originality. Vlaminck was himself a strong Fauvist painter.

The term “Fauvist” was originally derogatory, referring to its practitioners as “wild beasts” for their color choices, among other things. It’s stunning to think, now, that such a term of abuse, as if the people doing the rejections didn’t understand that when they stamped “outsider” on these artists, they were doing them the best favor they could. The complicated dance of moving from bold, maverick outsider to dominant insider wasn’t so well understood. This dance is now integral to modern art, maybe as a result of moving from a system of patronage to a system of half patronage and half popular estimation. (Only the rich can buy art, but ordinary people can line up to see blockbuster shows at museums.) Vlaminck did understand this dynamic, trumpeting his outsider status way after it was stale, as a way to claim permanent authenticity.

Vlaminck was attacked for not mixing his colors, using them as they came from the tube, and sometimes smearing the paint right onto the canvas from its tube. “Village road,” 1911 has that blur:

Van Gogh did this as well. The resulting basic colors are bold, jarring, and powerful. The smeared paintings are disturbing, surreal, and represent a whole other vector of strangeness within his Fauvist work.

Sometimes his work is even more painterly than Fauvism regularly achieved, as in the “Blue Still Life,” (1907, above) which has random painterly orange marks, as if to remind you of the artifice and process, reminiscent of some Renaissance paintings with magical elements that pop out of the level of realism the rest of the painting establishes. See below, “Bougival,” 1905, in which Vlaminck’s tree on the right is so abstract that it seems to belong in another painting, as if this were Warhol painting on top of Basquiat:

Some of the work is stunning. “La Grenouillère” (1905, below) looks like an illuminated screen from across the room. Vlaminck was an original painter, working with style breakthroughs he and others invented.

Vlaminck’s Cubist Puzzle

Vlaminck later experimented with Cubism before evidently becoming jealous of Picasso’s success and writing rejections of Cubism. Perhaps he tried out Cubism (see “Opium,” 1910, below) to avoid being left behind, or perhaps because he thought he could repeat his success at placing himself in the avant-garde as he did with Fauvism. After WWI, in which he served as a soldier in Paris (he was 38 in 1914), he stopped making cubist work. You can’t always tell where the light is in the painting, but in some places, you can. The light on the face is coming from the viewer’s left, and the same is true of the pitcher on the lower left. There is nothing to contradict this idea of the light coming from the left. The shapes look Cubist, as does some of the flatness, but there is also some depth formed by light and perspective, especially around the head. The painting uses “the visual language of Cubism,” but not all of its ideas.

Vlaminck’s relationship with Cubism was fraught. See this account:

He related how he "was suddenly confronted with a Cubist painting at Paul Guillaume's gallery as late as 1914" and at that moment "was no longer on [his] own ground." It was as though, declared Vlaminck, "I was on the brink of an abyss." His bitterness towards Cubism developed from the belief that the style had usurped the role of Fauvism in the unfolding of modernism. He blamed Picasso, whom he "regarded as a trickster and an imposter." Despite these virulent attacks, he claimed in his book Tournant Dangereux (1929) that he was directly involved with the birth of the movement during a "lively art discussion" at a small bistro. While he can be credited with the discovery of the inspirational African sculptures in Argenteuil in 1902 and selling a mask to Derain, his direct involvement in the movement was short-lived.

I am imagining the mid-life crisis of this man, happening at the same time (1914) as the world was self-destructing. Yet his reaction seems petty and small. A more impressive man might’ve stood aside to celebrate someone else’s visual achievement. Or jumped more decisively on that train. His Cubist work is very good. Perhaps he didn’t think so, or had trouble with a pivot in identity. At some point, he decides that keeping up with the avant-garde is not his bag any more.

When he tries Cubism, he refuses to mess up the light. In the Cubist “Still life,” 1910, the comment tells you how the artist is unlike Picasso while being inside of his language for this reason. The light is all from the viewer’s left:

As I look at it, I feel the way it challenges me less than the Picasso/Braque pre-WWI Cubist paintings that do mess with where the light comes from, deliberately being inconsistent about that. Is Picasso “more of a genius” for being willing to get the light mixed up? For being willing to go that far, if messing the light means going farther? What does going father, as opposed to being perverse, mean in this case?

Rabid Picasso-worship only gets in our way as we consider this problem of innovation and credit. However, the problem of innovation and credit won’t go away if we try to say that it is not what matters. It very much does matter unless we discount the entire modern art story of itself as the machine of great innovations, and its claim for itself that art means re-making the act of seeing.

Vlaminck’s War

Power and responsibility are inseparable. Eventually, during the occupation of France in the 40s, Vlaminck denounces Picasso and Cubism, and in doing so, courts Nazis who are courting him. He takes up an invitation from Goebbels and visits Germany along with other French artists such as Derain. Later, he claims that this action was to get some prisoners released. (After the war, it was so typical of French individuals to claim membership in the tiny and ineffectual Resistance that if everyone who claimed to be in it were actually so, they could have overthrown ten such occupations.) The show documents Vlaminck’s intellectual collaborations with the Nazis. He was both denounced by them and ironically lumped in with all the other moderns the Nazis called “degenerate.” Vlaminck wrote articles praising the vitality of Nazi culture even as his work was being taken out of museums by them (and also looted by them.) It is tempting to see his denunciation of Cubism as clownish jealousy, or to see his occupation actions naïve, except that if he had only denounced Cubism without resorting to sucking up to Nazis, his reputation would be damaged but not broken. After WWII, he was “prohibited from showing his work for one year due to his political stance during the occupation.” (Text from the Barberini exhibition.) The museum said there hadn’t been a retrospective of Vlaminck in Germany in 100 years. No wonder. They had to be thinking that his aesthetic importance and the distance from when he was a Nazi suck-up to now makes such a show a good idea.

Irony: “Vlaminck’s work was shown at documenta 1, the first international show after the Second World War. The exhibition was dedicated to art that had been defamed as ‘degenerate’ during the Nazi era.” (Barberini text.) Is Vlaminck an outsider when the Nazis call his work degenerate, or an insider?

I’m glad I saw this show. I haven’t seen Fauvist art that was new to me in decades. I don’t believe in canceling artists, though I might not want to go see a Leni Riefenstahl film series.

The first time I encountered intellectual collaboration with Nazis was when I was in grad school for English literature and read articles Paul de Man wrote while living in occupied Europe during the war. They formed for me a template of what conformity means. I would like to fancy myself allergic to conformity, and it still disgusts me to see it in Vlaminck’s case, but now I prefer to wonder how unconsciously conformist I am, without giving up the right to judge others. De Man’s self-prostitution includes 200 articles written for anti-Semitic publications and a suggestion that if all the Jews in Europe were carted off to some non-European location, European culture wouldn’t suffer. After that oeuvre of De Man’s work was discovered in 1987, and was defended as not necessarily anti-Semitic by his surviving friend Jacques Derrida, the power of the Deconstruction school in American literary criticism collapsed (though it’s hard to say there is cause and effect there).

In theory, a philosophy should be immune from the malfeasance of its practitioners, even of its inventors. But the power of the intellectual scene is too great to resist. By this point, when I think of Deconstruction, its claim to be able to show contradictory elements of any text gives me the willie’s. Mentally, I go straight to Kellyanne Conway’s “alternative facts,” vintage of the Trump administration of 2017. When does sophistication descend into mere lies? Postmodernism is all fun and games until someone loses an eye.

The museum doesn’t shy away from the problems Vlaminck poses. In their articles on him, for instance, there’s a discussion of how Vlaminck seems to have had his messed up relationship to power, credit, and originality since he was a young man. See here: “In his writings, Vlaminck never tired of reminding readers of his role as an outsider in the Paris art world.” Yet by 1906 he has a dealer (Vollard) who finances Vlaminck well enough that he no longer has to do anything to pay his bills but paint. He’s thirty. Outside of what?

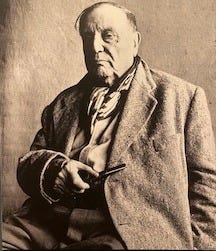

A Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man

At the end of the show, the problem of Vlaminck apparently becoming unable to keep innovating comes to the center. I was ambivalent about this claim. I’m ready to say Vlaminck was a collaborationist whore even as I am happy to say his art is nevertheless very much worth looking at, but whether he should have innovated all his life is another question. This view of his creative arc is well-established. See this article from 1977 by Charles Millard. The late paintings show a development of the older ones, but not a new conceptual breakthrough. Did he stagnate?

Did Louis Armstrong stagnate because he never became a Bebop musician? Some of the Bebop musicians thought so but does anyone think so now? See Terry Teachout on this history. The Dizzy Gillespie v. Louis Armstrong conflict seems far away from Vlaminck and the Cubists, but is it?

Isn’t there a massive contradiction between the idea that an artist must innovate versus the liberal (left-sociological) idea, as in literary naturalism, that each person is the product of their environment? That is, aren’t the same people saying at once that Art = A Conceptual Breakthrough and that rightists grossly exaggerate individual agency/responsibility?

Does anyone still believe in Foucault’s “death of the author”? Does anyone think that “language” produces literature, and not individual artists? That idea makes some sense if literature is seen from the moon. It’s not a model of the experience of reading an actual book. Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (in which “responsibility” gets a big play in chapter 1) and Michael Chabon’s Yiddish Policeman’s Union (in which the Jews in the book are products of their alternate historical facts) are not “language.” They are novels that come from individual minds. Isn’t the idea of naturalism (we are products of our backgrounds) suspiciously convenient for the left’s attempt to absolve individuals of responsibility for being unsuccessful financially? Isn’t individualism suspiciously convenient for the right’s attempt to blame individuals for whatever happens to them and thus prevent socialism from happening in our society?

Vlaminck gets credit in some Barberini posts as inspiring Expressionist use of heavy outlines, yet he doesn’t move on into Expressionist art himself. He remains a Fauve. Or does he? His color contrast seems derived from Fauvist ideas of color, but something distinct. What are the proportions of innovation and community in Vlaminck’s Fauvist and quasi-Cubist paintings, and in his tube-smear paintings, and then later, in his surreal-color paintings, which are a kind of super-Fauve genre unto themselves:

Can I have my socialist politics while still saying an artist like Vlaminck was both his own and his community’s? His art is meaningless outside of the small community of like-minded people; it is of its time and place. In fact, he is more of a community-based artist before The Great War than after World War Two, when no one is still doing Fauvism or trying to deepen it. Even before 1914, his art is not exactly like anyone else’s from that Parisian community. His act of intellectual collaboration during WWII with tyrannical oppressors is a perfect example of an individual’s response to the community around him. In this case, the response was poor.

Does anyone question the centrality of innovation in art nowadays? (Why do we uncritically accept as self-evident the idea that art must innovate, as opposed to holding a mirror up to nature, as pre-French-Revolution artists thought?) Didn’t Vlaminck himself claim innovation as a key to his own self-branding? His railing against Cubism was, in part, more self-fashioning as the “outsider.” (But self-fashioning and artistic innovation are not the same.)

This late painting is reminiscent, in its startling color contrast, with “La Grenouillère” of 45 years earlier. It’s the same artist, a person with his own way of seeing. This work deepens and furthers the older work.

Another way to think about the artist’s relation to other people is to consider the artist as a perceiving mind that thinks. The mind uses senses to receive information (in Locke, “impressions”) from the outside world. The artist sees the world, and paints. We get landscape paintings. The world the artist sees is determined, in part, by other people, and in part, by objective facts, as, for example, if one’s cities are on fire. Note the date, 1945.

“The Fire” shows the results of Allied bombs. It recalls the contrast in John Martin’s painting of Pandemonium (hell). The world is Vlaminck’s subject, but the color-contrast is the way he sees. He might never have seen this way without other people, Cezanne and other Fauves, showing him, and he showing them, how to see via paint.

This is a thoughtful and well-informed essay that deftly captures certain dynamics of a half century of political and artistic turmoil. But who now cares if artists and intellectuals we prize capitulated to national socialism? Some people, perhaps, who boycott their work, but most overlook it even while not excusing them. Boycotting a work of art or literature does not extinguish it, though it is morally useful to know how its creator failed to stand up to principles.

I take minor issue with "... the problem of innovation and credit ... very much does matter unless we discount the entire modern art story of itself as the machine of great innovations, and its claim for itself that art means re-making the act of seeing."

I do not think that "re-making the act of seeing" (or hearing or reading, for that matter) is limited to modernists. It has been the province of all artistic endeavors, from time immemorial, to make us ponder the process of change.

What we call "modern art" emerged from the satanic mills of industrial technology that had been transforming work, leisure, values, and everyday life for the better part of a century. Since life was changing, so must holding up a mirror to it reflect differently.

And so it is today, as the world becomes digital and embedded non-human intelligence speaks to us from server farms, just as the actual farms that sustain us dry up and blow away; a time of (accelerating) change. Who are the artists who grasp this great transformation well enough to suggest new ways of seeing, being, and acting? Some, like Vlaminck, will chose to ride the wave. Others will resist. All, in the end, may be swept away.

Art: RIP